Featured News

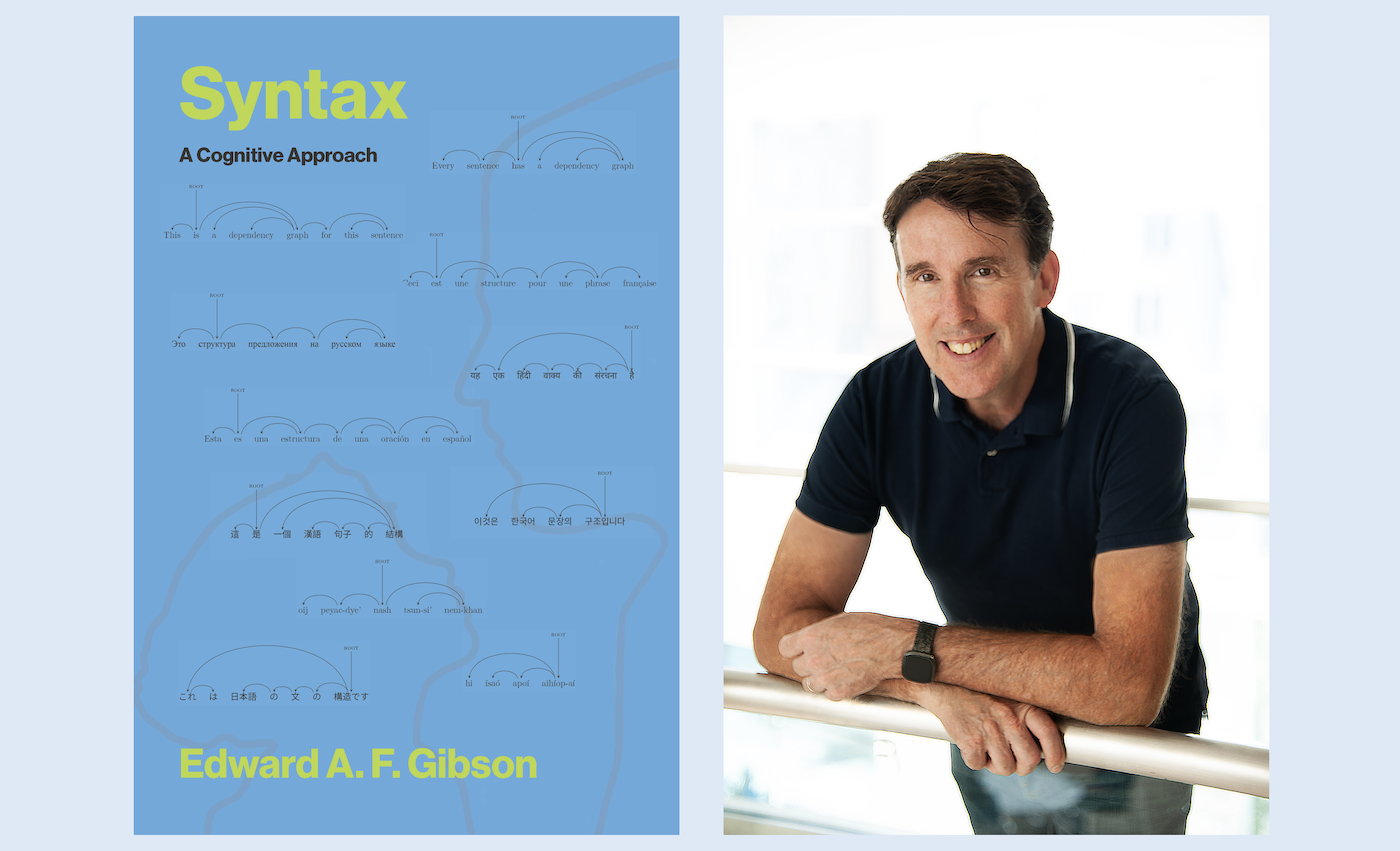

For decades, Professor Ted Gibson has taught the meaning of language to first-year graduate students in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences. A new book, Gibson's first, brings together his years of teaching and research to detail the rules of words, as he sees them.

“I actually don't think the form for grammar rules is that complicated,” Gibson says. “I've taught it in a very simple way for many years, but I've never written it all down in one place.”

"Syntax: A Cognitive Approach," released by MIT Press on December 16, lays out the grammar of a language from the perspective of a cognitive scientist, outlining the components of language structure and the model of syntax that Gibson advocates: dependency grammar.

It was his wife and research collaborator, Associate Professor Brain and Cognitive Sciences and McGovern Institute Investigator Ev Fedorenko, who encouraged him to put pen to paper.

"She suggested a paper," Gibson says. "It turned into a book."

Featured News

Led by Jim DiCarlo, the Peter de Florez Professor of Neuroscience in the MIT Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, the initiative previously known as the MIT Quest of Intelligence has been renamed in recognition of a gift from the Siegel Family Endowment.

The gift will enable further growth of the MIT Siegel Family Quest for Intelligence (SQI) research and activities. Its mission remains the same: to comprehend how brains produce intelligence and how it can be replicated in artificial systems to address real-world problems that exceed the capabilities of current artificial intelligence technologies. is enabling further growth in SQI’s research and activities.

“Ours is the only unit at MIT dedicated to building a scientific understanding of intelligence while working with researchers across the entire Institute,” DiCarlo says. “There has been remarkable progress in AI over the past decade, but I believe the next decade will bring even greater advances in our understanding of human intelligence — advances that will reshape what we call AI. By supporting us, David Siegel, the Siegel Family Endowment, and our other donors are demonstrating their confidence in our approach."

Along with DiCarlo, who is the director of SQI, Professor of Brain and Cognitive Sciences Josh Tenenbaum is SQI's director of science, and Eugene McDermott Professor in the Brain Sciences Tomaso Poggio is scientific advisor. It is a research unit in the MIT Schwarzman College of Computing.

Featured News

Our thoughts are specified by our knowledge and plans, yet our cognition can also be fast and flexible in handling new information. How does the well-controlled and yet highly nimble nature of cognition emerge from the brain’s anatomy of billions of neurons and circuits? A study by researchers in The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory at MIT provides new evidence that the answer might be found within a theory called “spatial computing.”

First proposed in 2023 by Picower Professor Earl K. Miller and colleagues Mikael Lundqvist and Pawel Herman, spatial computing theory explains how neurons in the prefrontal cortex can be organized on the fly into a functional group capable of carrying out the information processing required by a cognitive task.

In the new study, lead author Zhen Chen and other current and former members of Miller’s lab put spatial computing to the test by examining whether five predictions it makes about neural activity and brain wave patterns were actually evident in measurements made in the prefrontal cortex of animals as they engaged in two working memory and one categorization tasks. Each prediction held true.